The Ironwood – An Introduction to Google TPU Rack & Optical Circuit Switch System

Today, I would like to introduce the Google Ironwood TPU rack and its Optical Circuit Switch (OCS) system, which have recently attracted much attention from investors.

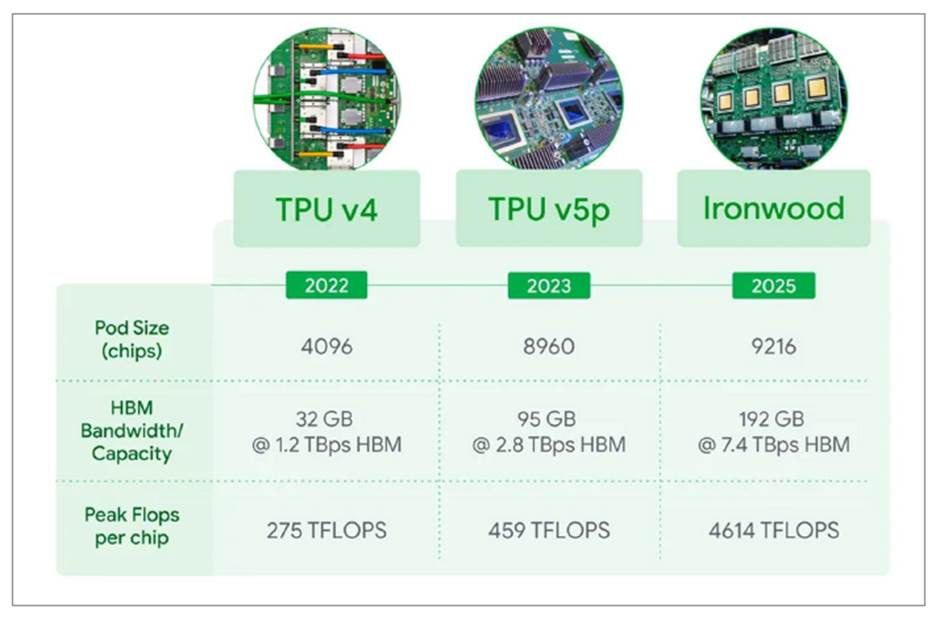

First of all, let’s clarify one thing: although Google claims Ironwood to be its seventh-generation TPU, the table below shows that Ironwood (also known in the system vendors as Ghostfish) is actually its original TPU V6p (see figure below); The so-called eighth-generation TPUs to be launched by Google next year—Sunfish and Zebrafish—are in fact its original TPU V7p and TPU V7e respectively (for details, please refer to my article from last year: The Accelerator War – AWS Tranium, Google TPU, Habana Gaudi and Others). It’s just that Google has now played the naming game, renaming the original TPU V6e to TPU V6, the original TPU V6p to TPU V7, and the original TPU V7p and TPU V7e to TPU V8ax and TPU V8x.

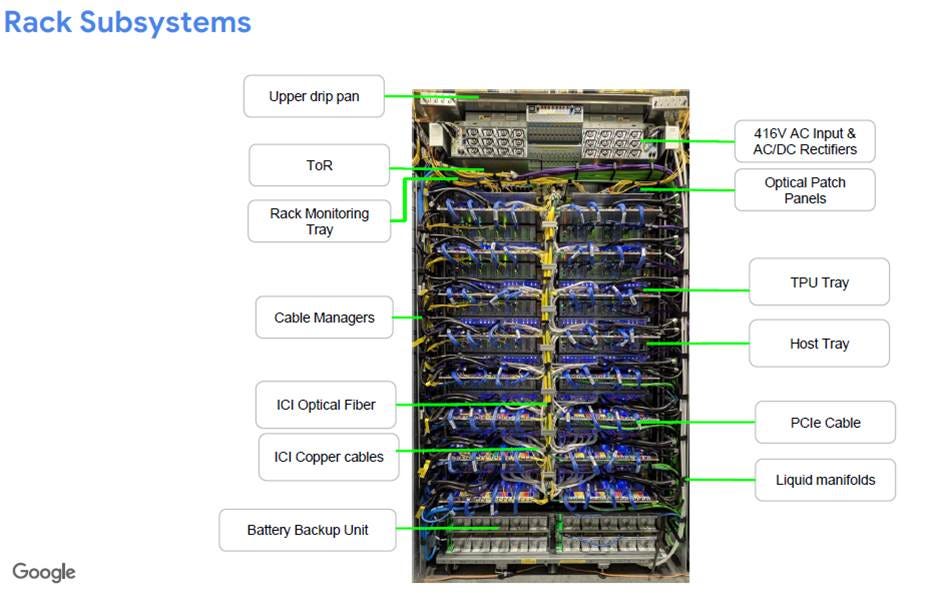

A TPU rack contains 16 TPU trays, each TPU tray housing 4 TPU chips, so a single TPU rack has a total of 16 × 4 = 64 TPU chips. At the same time, the TPU rack is also equipped with CPU Host trays (see figure below), with the CPU-to-TPU ratio typically being 1:4. Therefore, the four million TPUs expected next year roughly correspond to one million CPUs (this was mentioned in my previous article talking about GUC: Marvell (MRVL US) vs. Broadcom (AVGO US) vs. Alchip (3661 TT) vs. GUC (3443 TT) – A Brief Update on ASIC Plays).

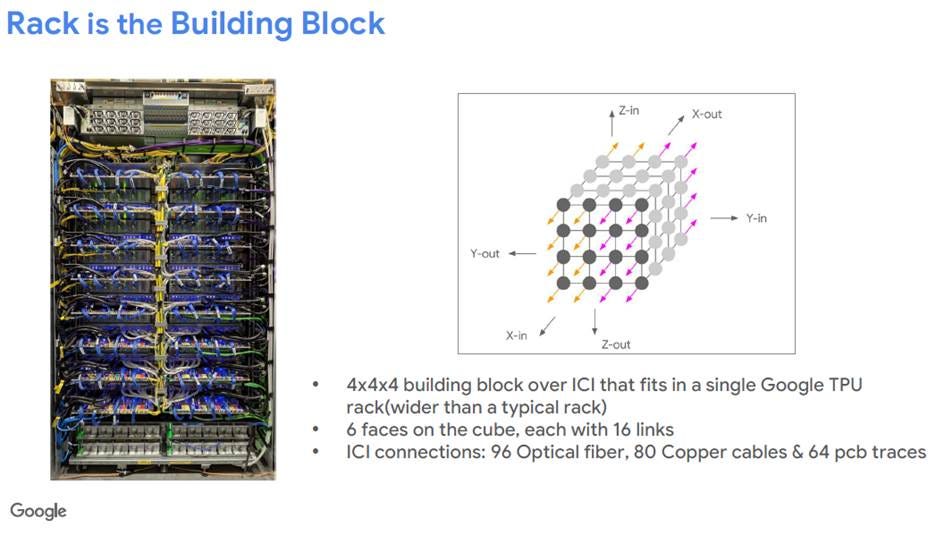

Google TPUs adopt a 3D Torus interconnect architecture that can be abstracted into a 4 × 4 × 4 cube (i.e., 64 TPU chips in total): each cube has six faces, and the 16 TPUs on each face (4 × 4) connect to external OCS switches. Theoretically, the six faces require 16 × 6 = 96 connections, but the two points on opposite faces connect to the same switch, so only 96 / 2 = 48 OCS units are actually needed; meanwhile, the TPUs inside the cube are interconnected by cables or PCBs (see figure below):

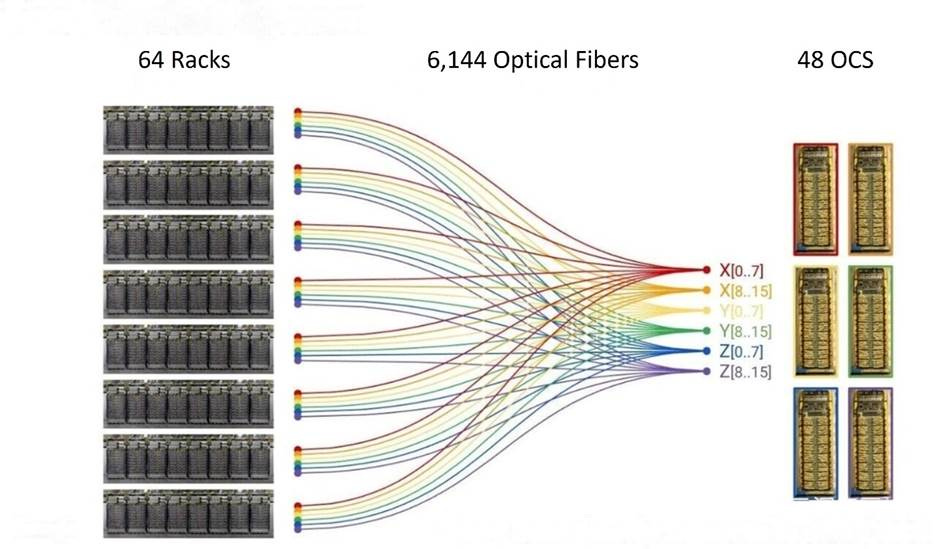

By using TPU V4 as an example, let me explain how the 4096 TPUs in a single Google pod are interconnected through OCS switches:

- As stated earlier, a TPU rack contains a total of 64 TPU chips, and a TPU V4 pod can include up to 64 TPU racks, so a pod contains 64 × 64 = 4096 TPU chips.

- As mentioned earlier as well, a TPU rack has 96 optical ports, so 64 racks correspond to a total of 64 × 96 = 6144 optical ports.

- Google currently uses mainly 136-port OCS switches, of which 128 ports are effective (the details to be explained later). Therefore, 48 OCS switches correspond to a total of 48 × 128 = 6144 ports, matching exactly the 6144 optical ports of a TPU V4 pod. The ratio of TPUs to optical modules is 4096:6144 = 1:1.5 (see figure below):

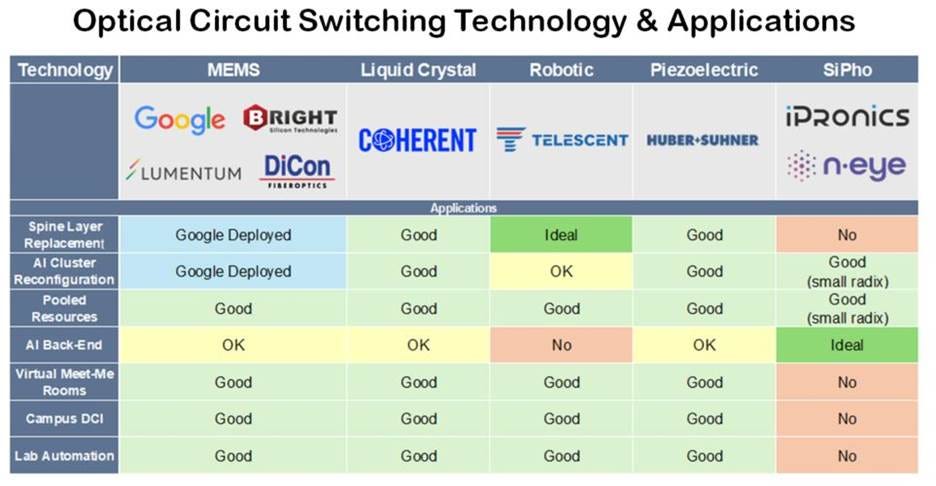

Here is a brief introduction to the OCS that Google currently uses. We know that conventional data centers use electrical packet switches. In such architectures, signals passing through electrical switches undergo multiple conversions between electrical and optical signals. Each packet’s signal processing incurs substantial power consumption and increases data latency. As network traffic in AI data centers skyrockets, Google uses optical circuit switches to replace traditional electrical packet switches mainly to reduce power consumption and cost. OCS switches come in various technological types—commonly seen in the industry are MEMS, liquid crystal, robotic, piezoelectric, and silicon-photonics OCS. Google’s current in-house and deployed solution is MEMS OCS (see table below):

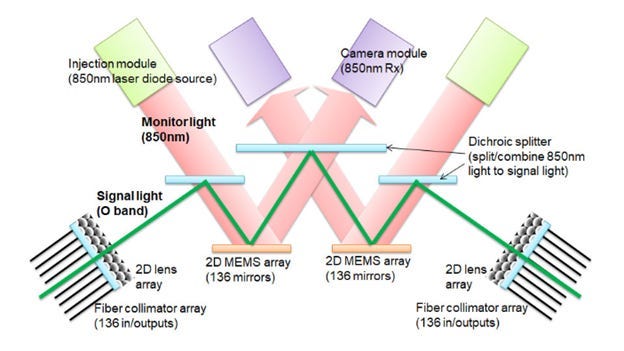

The internal structure of Google’s MEMS OCS switch is shown below. The input and output are two fiber collimator arrays, each consisting of a fiber array and a micromirror array, with 136 channels on both input and output side. After light enters the OCS system through the fiber, it passes sequentially through two 2D MEMS arrays. Each MEMS array contains 136 micromirror units, each with independent drive control. By applying different electrical signals, the required mirror tilt angle is achieved, precisely adjusting the propagation direction of the signal light (see the green line in the figure below). In addition, the system includes two monitoring channels, corresponding to the thick red lines in the figure below. The monitoring channels use 850-nm light, which is reflected by the MEMS array and enters the monitoring camera. Feedback control of the MEMS array is then carried out via image processing to optimize link insertion loss. As mentioned earlier, the effective port count of Google’s 136-port OCS switch is actually 128, because 8 of the 136 micromirrors in the MEMS array are reserved for monitoring and calibration purpose (see figure below):

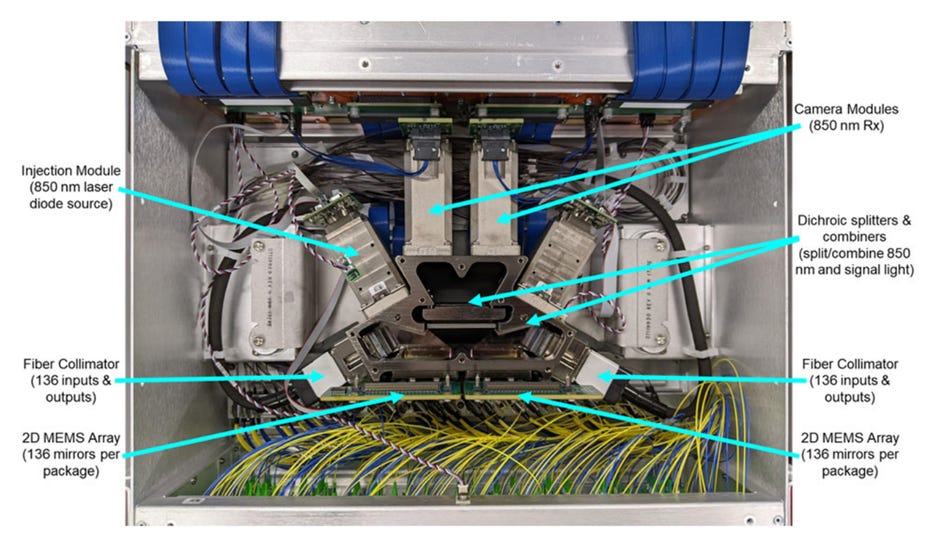

An actual image of Google’s MEMS OCS switch is shown below:

It should be noted that beginning next year, Google’s MEMS OCS will be upgraded from the 128-port switches used this year to the next-generation 300-port switches. Next, using Google’s newly released Ironwood/ TPU V7 as an example, I will explain how the 9216 TPUs in a pod are interconnected through OCS switches:

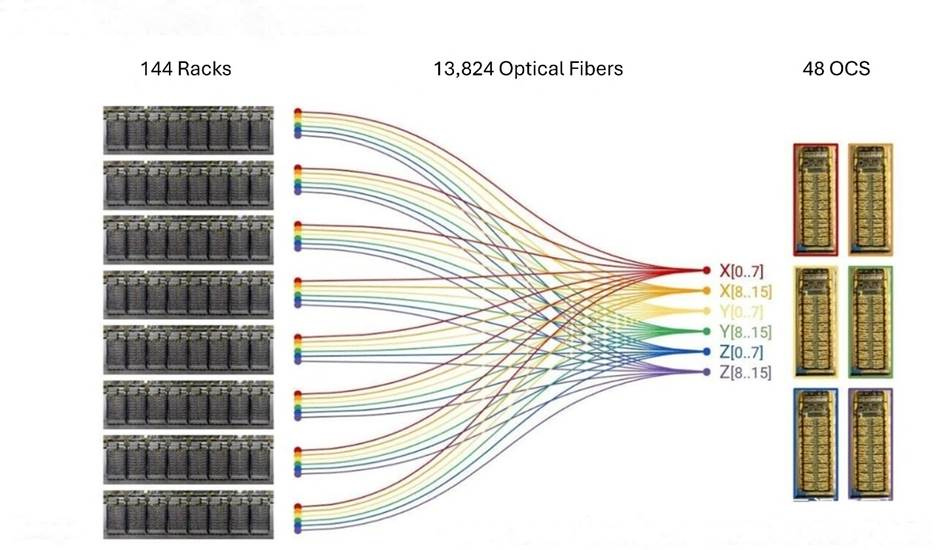

- As stated earlier, a TPU rack contains a total of 64 TPU chips, and a TPU V7 pod can include up to 144 TPU racks, so a pod contains 64 × 144 = 9216 TPU chips.

- As mentioned earlier as well, a TPU rack has 96 optical ports, so 144 racks correspond to a total of 144 × 96 = 13824 optical ports.

- Next year Google will mainly use 300-port OCS, of which 288 ports are effective. Therefore, 48 OCS switches correspond to a total of 48 × 288 = 13824 ports, matching exactly the 13824 optical ports of a TPU V7 pod. The ratio of TPUs to optical modules is 9216:13824 = 1:1.5 (see figure below). It should be noted that beginning with Ironwood/ TPU V7, Google will use 1.6T optical modules, which is one of the reasons why Google’s demand for 1.6T modules will surge in 2026:

My supply-chain research shows that Google will need about 15,000 units of 300-port OCS switches in 2026 (primarily for AI LLM training), of which about 12,000 units will still be Google’s in-house OCS (which is contract-manufactured by Celestica), while the remaining roughly 3,000 units will be purchased externally—currently planned to be allocated between Lumentum and Coherent. The mass-production price of a 300-port OCS switch is expected to be between USD 100,000 and 120,000. Assuming next year’s 3,000 externally-purchased OCS switches are split equally between Lumentum and Coherent, each company could see USD 150mn–180mn in revenue contributions. Of course, aside from Google, both Lumentum and Coherent have their own additional OCS customers (eg. Lumentum: Microsoft, Meta; Coherent: NVIDIA, Oracle).

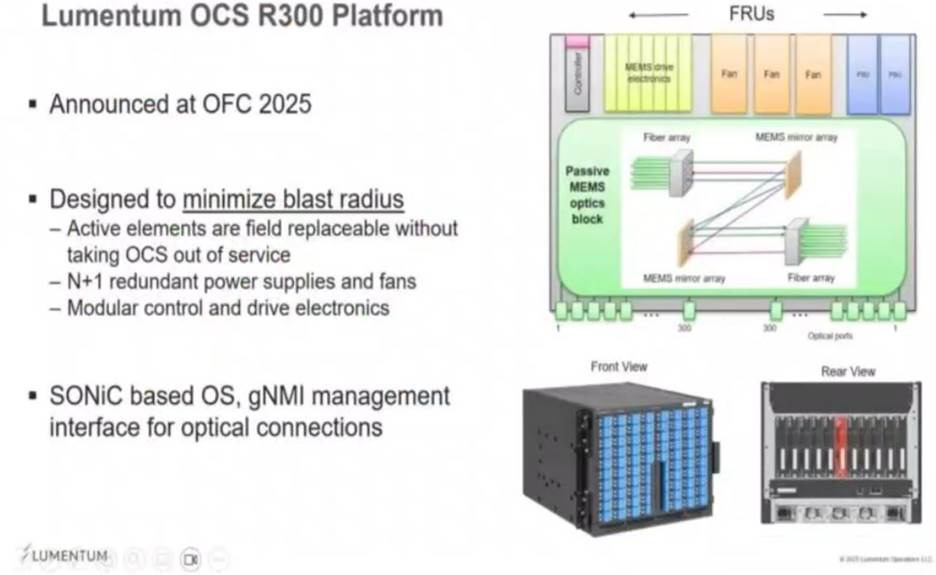

It is worth noting here that Lumentum and Coherent use different OCS technologies. Lumentum uses a MEMS OCS switch identical to Google’s in-house solution (see figure below):

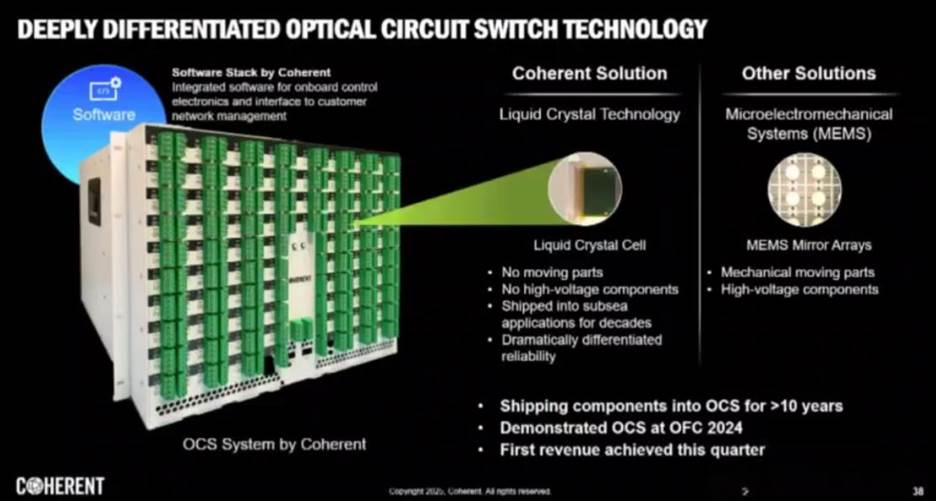

Coherent, on the other hand, uses a different Digital Liquid Crystal solution. In short, Digital Liquid Crystal (DLC) technology controls the orientation of liquid-crystal molecules via electrical signals to dynamically modulate the phase or polarization state of light, enabling beam steering and routing without the mechanical motion of traditional MEMS components (see figure below). Compared with MEMS OCS, DLC OCS is cheaper and requires lower drive voltage, but its switching time is much longer than that of MEMS devices, making it unsuitable for OCS applications requiring frequent path switching. Fortunately, Google’s AI training clusters only need to switch optical paths about once per week, so DLC OCS is also viable:

Last but not least, as a bonus point for this article, I will introduce a little-known Google Ironwood play to readers in the following paragraphs.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Global Technology Research to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.