Is This Time Different? – How Will AI Large Language Model Bring the Memory Supercycle?

In today’s article, I would like to provide a comprehensive, top-down analysis of the memory demand of large AI models, a topic of recent investor concern. Since I primarily focus on the semiconductor and hardware industries and have limited research into the algorithms behind large AI models, I invited a close friend of mine,

, who has studied and researched large AI models at a top North American university, to analyze the actual demand of HBM, DRAM, and NAND for generative AI reasoning from an algorithmic and application perspective.The following calculations use ChatGPT-5 as an example. However, due to the limited public information disclosed by Open AI, some assumptions are based on our own estimates. Also, we have significantly simplified the model in order to clearly illustrate the demand logic within the limited space. Readers are welcome to adjust it based on their own assumptions.

We know that in the past, large model training was the core driving force behind the demand for the entire AI infrastructure; but now, inference workloads are rapidly becoming the dominant force. In other words, in the early stages of generative AI, computing power and capital expenditures were focused on the model training phase. At that time, the primary task of the storage system was to efficiently supply massive training datasets to thousands of GPU cores and periodically handle enormous model checkpoints to prevent catastrophic loss in the event of a training interruption.

However, today’s inference workloads are much more complex: they are a mix of various access patterns: for example, fully loading the model from storage (NAND) into memory (HBM/DRAM); offloading parts of the KV cache (HBM/DRAM) to storage (NAND) when it overflows and retrieving it later; and retrieving external data for RAG queries (NAND), among others.

Therefore, to understand the roles of HBM, DRAM, and NAND in LLM inference, one must first clarify the memory hierarchy of AI servers. Here we provide a brief layered explanation of this architecture:

Level 0: High Bandwidth Memory (HBM)

This is 3D-stacked DRAM directly integrated into the GPU package. Its sole purpose is to provide extremely high memory bandwidth to prevent GPU cores from “starving” while waiting for data.

Level 1: System DRAM

Typically DDR5 memory on the server motherboard, this is the next level in the memory hierarchy. Compared to HBM, DRAM offers larger capacity but lower bandwidth and higher latency.

Level 2: NVMe NAND Flash

This is the fastest persistent storage layer in AI servers, bridging the huge performance gap between DRAM and HDD.

To more specifically illustrate how each layer collaborates during the LLM inference process, let’s trace the data flow path of a typical GPT query request within the system:

(1) Request Arrival: The prompt input by the user first reaches the inference server.

(2) Model Loading: The server needs to verify whether the target model is already resident in HBM or DRAM. If the model has not yet been loaded, it will read the corresponding weight files from the local NVMe SSD.

(3) Prefill Stage: The model processes all tokens in the input prompt in parallel and generates the initial KV cache in HBM/DRAM, this serves as the model’s “short-term memory.”

(4) RAG Retrieval (if enabled): If the model has retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) enabled, the system sends a query to a vector database, which is typically also stored on NVMe SSD, to retrieve the context most relevant to the current prompt.

(5) Token Generation and Cache Growth: The model begins generating the output sequence token by token. With each new token, the KV cache grows. If the total cache size exceeds the available capacity of HBM/DRAM, the system will offload part of the KV data to the NVMe SSD so it can be read back as needed during subsequent inference.

(6) Logging and Persistence: The final model response and interaction metadata are written to storage, which is also handled by the NVMe SSD layer.

Through the above process, we can more intuitively see that the demand for HBM and DRAM during the LLM inference stage mainly comes from the following two aspects:

1. Static Memory for Model Weights:

This is the most direct portion of memory consumption. Before the model can start serving, all its parameters (including all experts) must be loaded into the GPU cluster’s DRAM. This ensures that any expert can be invoked immediately when selected by the router. If expert parameters are still on other storage, the latency from on-the-fly reading would be unacceptable.

2. Dynamic Memory for KV Cache:

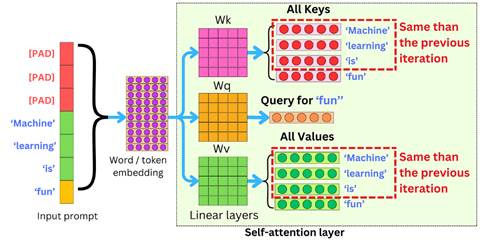

As we know, the generation process of LLMs is auto-regressive. Each time the model generates a new token, it appends that token to the input sequence and recalculates the attention weights for the entire sequence. Without optimization, this repeated computation would result in massive compute waste.

The KV cache (Key-Value Cache) was designed to solve this issue: during the first computation, the model stores the K and V vectors of each token in the cache; later, when generating new tokens, it only needs to compute Q/K/V for the newest token and retrieve the rest of the historical vectors from the cache.

This design boosts LLM inference speed by several times. It can be said that without the KV cache, the smooth interaction of modern chat models would be nearly impossible.

Source: The AiEdge

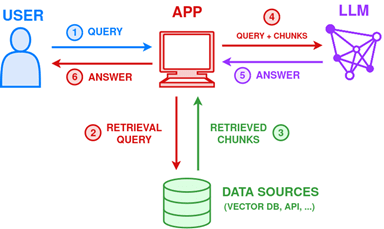

The demand for NAND during the LLM inference stage mainly comes from Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), while the storage of model weights, KV cache, and logs/results accounts for a relatively smaller proportion and will not be analyzed in detail here.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), in essence, allows the model to “look up information” before answering a question. Its process can be divided into three steps:

Retrieval: The system uses a vector search engine to find the segments most relevant to the user’s question from an external knowledge base.

Augmentation: The retrieved content is concatenated with the original prompt to form an “augmented” prompt.

Generation: The model combines the newly added context with its own semantic understanding to generate the final output.

RAG enables LLMs to access real-time, domain-specific external knowledge, thereby improving accuracy, traceability, and timeliness, and reducing the occurrence of hallucinations. The underlying large-scale vector databases typically reside on NVMe SSD clusters based on NAND, making RAG queries and context loading a key part of NAND read/write operations.

Source: www.ridgerun.ai

In the following paragraphs, I will use the above three factors to calculate LLM’s demand for HBM, DRAM, and NAND in detail. At the end of the article, I will also introduce a lesser-known memory-related stock to readers.