From CNN (Convolutional Neural Network) to Transformer

Disclaimer: This newsletter’s content aims to provide readers with the latest technology trends and changes in the industry, and should not be construed as business or financial advice. You should always do your own research before making any investment decisions. Please see the About page for more details.

In the last year’s article, I used ChatGPT-5 as an example to estimate the memory demand of AI large language models (Is This Time Different? – How Will AI Large Language Model Bring the Memory Supercycle?). However, this article only made estimation for text models, while “text-to-video” multimodal models, taking OpenAI’s Sora as an example, have different memory needs. Therefore, in the next article, I plan to provide readers with a detailed estimation of Sora’s impact on memory demand.

Before that, in order to help readers understand the Diffusion Transformer model underlying Sora, we need to trace the evolution of AI algorithms so that everyone can understand the Transformer architecture more intuitively. Let us start with a relatively easy topic: why can everything be handled with Transformer?

In fact, before Transformer, the main protagonist of the AI world was CNNs (Convolutional Neural Networks). Simply put, CNNs taught machines how to “see,” while Transformer further enable machines to understand the complex relationships among different parts of data.

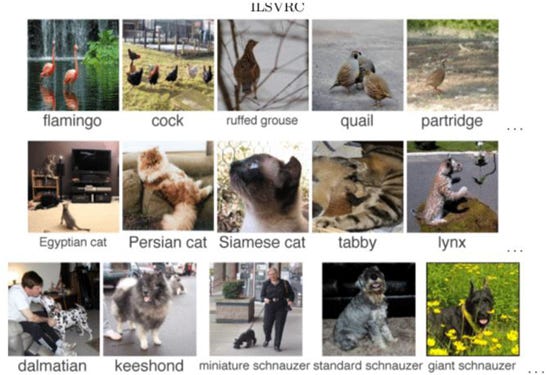

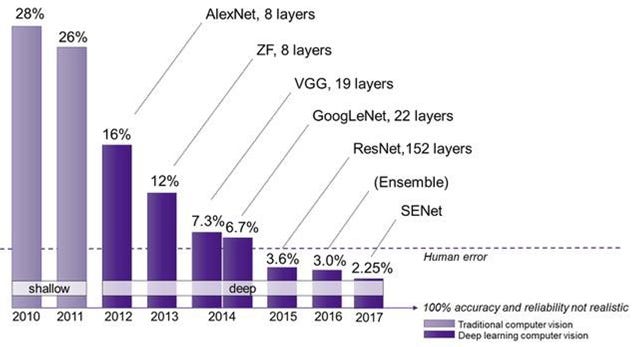

Going back to the time before 2012, the development of computer vision was slow, and mainstream methods relied on experts manually designing features, with unsatisfactory results. The real turning point came with the ImageNet competition (ILSVRC) in 2012. That year, a deep convolutional neural network called AlexNet burst onto the scene and won the championship with a Top-5 error rate of 15.3%, leading the second place by a full 10.8 percentage points. At that time, the error rate improvement in previous years had been only about 1% per year, and this leap was almost equivalent to compressing 10 years of industry research progress.

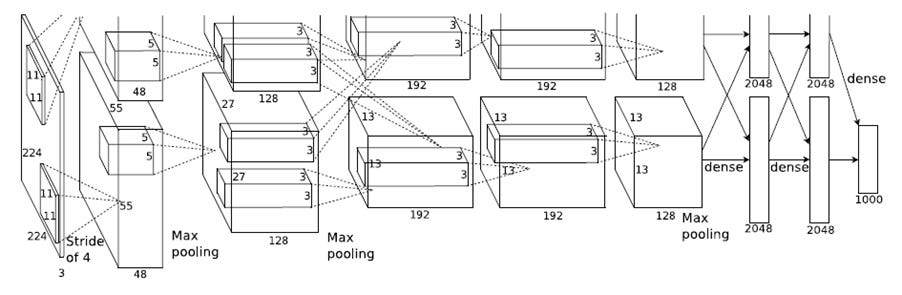

AlexNet’s victory sent two key signals: First, features automatically learned by deep neural networks can far surpass those manually designed by humans; Second, with the help of GPUs, training such large networks is entirely feasible in terms of computing power.

This “ImageNet moment” has thus been regarded as the starting point of the modern deep learning era. From then on, CNNs quickly became the gold standard in computer vision. Both academia and industry continuously introduced deeper and more complex architectures, from GoogleNet to ResNet, almost breaking performance records every year and creating a glorious period lasting a full decade. By 2015, CNNs’ recognition accuracy had even surpassed that of humans.

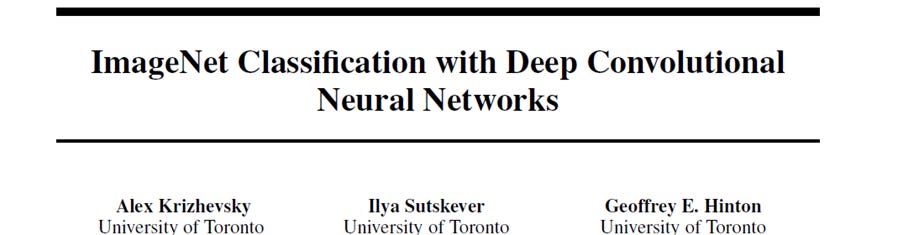

Here’s a little anecdote: Before AlexNet burst onto the scene, Geoff Hinton had long wanted to push academia to accept the value of neural networks. In the spring of 2012, he even specifically called Jitendra Malik at UC Berkeley, a professor who had publicly criticized Andrew Ng’s view that “deep learning will be the future of computer vision.” Hinton’s proposal was simple: why not just use the ImageNet dataset organized by Fei-Fei Li’s team to hold a competition? As we later learned, this competition completely rewrote history. The first author of that paper was Alex Krizhevsky, so this CNN was named AlexNet, igniting the application of deep learning in the field of computer vision. The second author, Ilya Sutskever, later became the well-known former CIO of OpenAI and is now the founder of Safe Superintelligence (SSI).

As for why GPUs were ultimately chosen, besides the well-known reason of “matrix parallel computation,” there were actually some lesser-known anecdotes. At the time, Krizhevsky had just finished learning CUDA, and Sutskever was also eager to try it out on ImageNet. The problem was that the dataset was too large: the training set was nearly 138 GB, and Krizhevsky once felt it simply could not be run. In the end, it was Sutskever who found a way to compress the images, which finally persuaded Krizhevsky.

The atmosphere in Hinton’s lab was also very much of its era: during training, people often gathered around the two GPUs running the models to “keep warm.” Hinton even approached Nvidia’s sales team hoping they could donate a few GPUs, but was politely refused. It was only later, after Jensen Huang heard about this, that he personally delivered a few GPUs. The rest of the story is familiar to everyone.

The success of AlexNet was not only about breaking competition records; more importantly, it allowed the world to see clearly for the first time that deep neural networks could indeed “see” images.

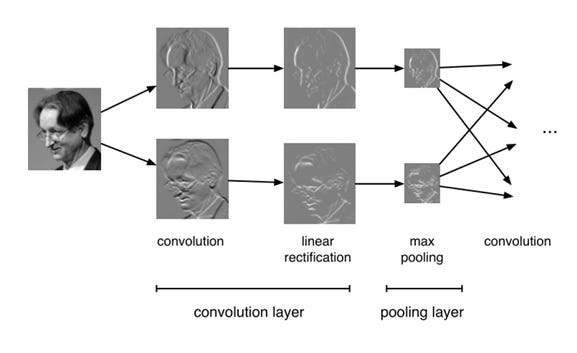

So how exactly does CNN achieve this? It can be imagined as a team progressing layer by layer, with the goal of identifying key objects (such as a cat) from an image:

· Convolutional layers are the core members of CNNs, like specialized detectives. Each convolution kernel looks for only one specific clue, such as vertical edges or color gradients.

· Pooling layers, most commonly max pooling, collect clues within a small region and retain only the strongest signal. This both compresses the data and reduces the computational burden of subsequent layers, and also brings about so-called “translation invariance”: whether cat ears appear in the upper left corner or slightly to the right, the model can still recognize the key information of “having pointed ears,” making it more robust.

· Fully connected layers aggregate and combine the abstract features extracted at the front end (“furry texture,” “two pointed ears,” “round eyes”). Finally, the fully connected layer gives a judgment: “Considering all clues, there is a 98% probability that this photo contains a cat.”

The subtlety of CNNs lies in stacking multiple convolution and pooling layers to progressively extract features, forming a bottom-up information processing hierarchy. This structure actually mimics biological visual systems, from simple patterns to complex cognition. Its success is largely due to the “inductive bias” built into the architecture.

The so-called “inductive bias” is not a flaw, but rather a set of “reasonable assumptions” preset in the architecture. The two core designs of CNNs—locality and translation invariance—are the most typical examples: convolution focuses only on local regions, assuming that “a certain feature (such as a cat’s eye) has a similar pattern no matter where it appears in the image.” In visual tasks, this assumption almost always holds, so CNNs can perform excellently even when data is not particularly abundant. But this “bias” is also a double-edged sword. When a problem requires crossing local regions and establishing long-distance relationships, CNNs become clumsy. Imagine a photo where a person on the left is holding a long fishing rod, and the rod tip extends to the far right of the image. For a CNN to associate the “hand” with the “rod tip,” signals often have to be passed layer by layer through multiple convolutions and pooling operations, which is extremely inefficient.

Therefore, just as CNNs were advancing rapidly in the visual domain, a new architectural revolution was quietly brewing in the field of natural language processing. In 2017, Google published “Attention Is All You Need,” proposing the Transformer architecture for the first time. In the following paragraphs, I will provide readers with a detailed explanation of the principles behind the Transformer architecture.

Substack now supports friends referral programme. If you enjoy my newsletter, it would mean the world to me if you could invite friends to subscribe and read with us. When you use the “Share” button or the “Refer a friend” link below, you’ll get credit for any new subscribers. Simply send the link in a text, email, or share it on social media with friends:

When more friends use your referral link to subscribe, you’ll receive special benefits:

- 5 referrals for a free 3-month compensation

- 10 referrals for a free half-year compensation

- 20 referrals for a free full-year compensation